Poor housing leaves its mark on our mental health for years to come

The damaging effects of housing disadvantage on people’s mental health can persist even years after their housing situation improves.

Australia carries an enormous and increasing mental health burden. At the same time, housing disadvantage is on the rise in Australia. Our latest research indicates the trends are related. A systematic review of the evidence shows housing disadvantage is harmful for mental health, and the effects stay with you well after your housing situation might have improved. For instance, living in an overcrowded house from birth to early childhood is associated with depression in midlife.

So how many people are affected? One in five Australians experience a mental disorder in any given year and nearly half will experience some form of mental illness during their lifetime. Mental health accounts for more than A$9 billion of public and private spending in Australia, and 4.2 million Australians received mental health-related prescriptions in 2017-18.

As for housing, up to 1.1 million Australians live in homes that are in very poor condition.

Making the link between housing and mental health

In recent years, several high-quality Australian and international studies have sought to understand the relationship between housing disadvantage and mental health. A small portion of this evidence base has attempted to rigorously quantify the effect of housing on mental health over an extended period. Bringing the results of such longitudinal studies together, we conducted a systematic review to establish whether housing disadvantage can lead to poorer mental health down the track.

Housing disadvantage includes overcrowding, falling behind on mortgage payments or rent, moving house often, insecure housing tenure, subjective perception of inadequate housing, eviction, or poor physical housing conditions. Our systematic review of international evidence shows that, regardless of how housing disadvantage is considered, there is a correlation with poorer mental health in future.

In the studies we reviewed, sample sizes ranged from 205 to 16,234 people. The follow-up period ranged from within one year to as long as 34 years across all life stages — birth to adulthood and old age. Despite deliberately excluding studies on the two extremes of homelessness and severe mental illness, we found each study confirmed an association between at least one marker of housing disadvantage and poor mental health.

The mental health outcomes included higher odds of depression, stress and anxiety. The studies included in the review detected these outcomes across all age groups from both very short follow-up periods of about two years to reasonably long periods over decades.

These findings make sense. Housing is a central part of our lives. It is, for most of us, our largest expenditure. It shapes our experiences; it is both a financial asset and a home.

This means insecure housing can be very destabilising for families and individuals.

Read more:

The insecurity of private renters – how do they manage it?

Our review highlights a great diversity of mechanisms through which housing affects mental health outcomes (such as anxiety and depression) at different stages of life. For example, physical housing problems such as damp or cold affect mental health in different ways to housing-related financial insecurities. But there is evidence that physical housing and affordability problems may work together to amplify the mental health effects.

Housing problems on the rise

The Australian housing system is changing and becoming less secure. More and more Australians are renting privately. Many young people will never own their own homes.

At the same time, our public housing sector can only provide a safety net for the most vulnerable people with high and complex needs. Waiting lists are long. And we’re seeing no substantive government commitment to reduce this shortage of social housing.

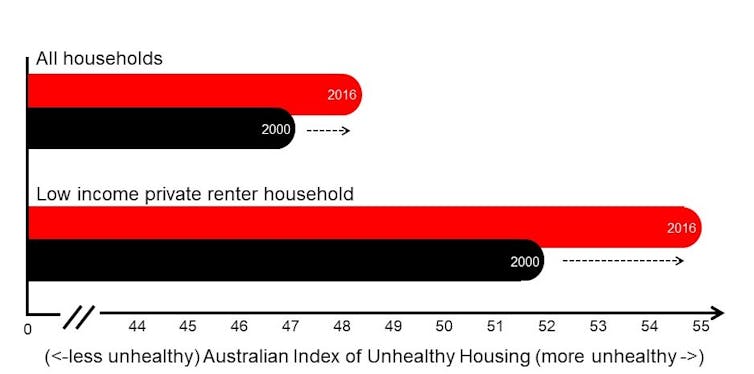

In addition, the quality of our housing is getting worse across the entire housing stock. The Australian Index of Unhealthy Housing is a composite measure of housing affordability, security, quality, location and accessibility. The index charts an increase in housing disadvantage across our housing stock since 2000, including a marked increase for low-income private renters.

Adapted from An Australian geography of unhealthy housing

Due to the growing unaffordability of housing, many of us simply cannot keep up with basic maintenance and repairs. Band-aid solutions mean some of us live with cold and damp housing, homes that leak when it rains, homes unable to accommodate growing families, or homes that may not support our needs as our mobility declines. At the most extreme end, 116,427 of us were homeless on census night.

Read more:

Chilly house? Mouldy rooms? Here’s how to improve low-income renters’ access to decent housing

On current estimates, one in every nine households has unaffordable housing. Up to 1.1 million Australians have housing that is in very poor condition (or even derelict).

Given the scale of housing disadvantage, its role in driving poor mental health should greatly concern us all. It suggests a large number of Australians will suffer with mental health issues related to, or worsened by, inadequate housing.

The changes in tenure and quality in the housing sector have been widely discussed. The mental health consequences of housing also need to be discussed and even prioritised.

Read more:

Housing: the hidden health intervention

Invest in housing for mental health

The Australian government’s latest research funding initiative, the Medical Research Future Fund, has a “Million Minds Mental Health Research Mission”. It aims to support research into the causes of mental illness, and the best early intervention, prevention and treatment strategies. Our systematic review suggests it is vital that both research and public investment directed towards improving mental health consider the affordability, quality and condition of people’s housing.

Housing is central to our lives. When it is affordable, secure and in good condition, it provides a foundation for us to participate fully in and contribute to society.

If we discovered a risk-free medication that protected people’s mental health, we would be clamouring for it to be made widely available. In considering the shape that housing policies might take, what if we thought of decent housing as a form of mass medication? A protective safety net? Wouldn’t it be something we’d invest in and prescribe for all?

Read more:

Is this a housing system that cares? That’s the question for Australians and their new government![]()

Ankur Singh, Research Fellow in Social Epidemiology, University of Melbourne; Emma Baker, Professor of Housing Research, School of Architecture and Built Environment, University of Adelaide; Lyrian Daniel, Research Fellow, University of Adelaide, and Rebecca Bentley, Associate Professor, Centre for Health Equity, Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image: Lovely Bird/Shutterstock