Ozanam House: Looking back and looking forward

From a men's night shelter to a purpose-built facility, Ozanam House represents an evolution in our response to homelessness. Written by Doug Harding, Senior Practitioner, VincentCare

The physical redevelopment of Melbourne’s three large night shelters (the Gill Memorial, Ozanam House and Gordon House) in the mid‑1990s was transformative for the homelessness sector in Melbourne at the time. It marked the end of the night shelter era, with dormitory style accommodation (200 to 400 men at each shelter), lining up for a room each night and vacating the building during the day.

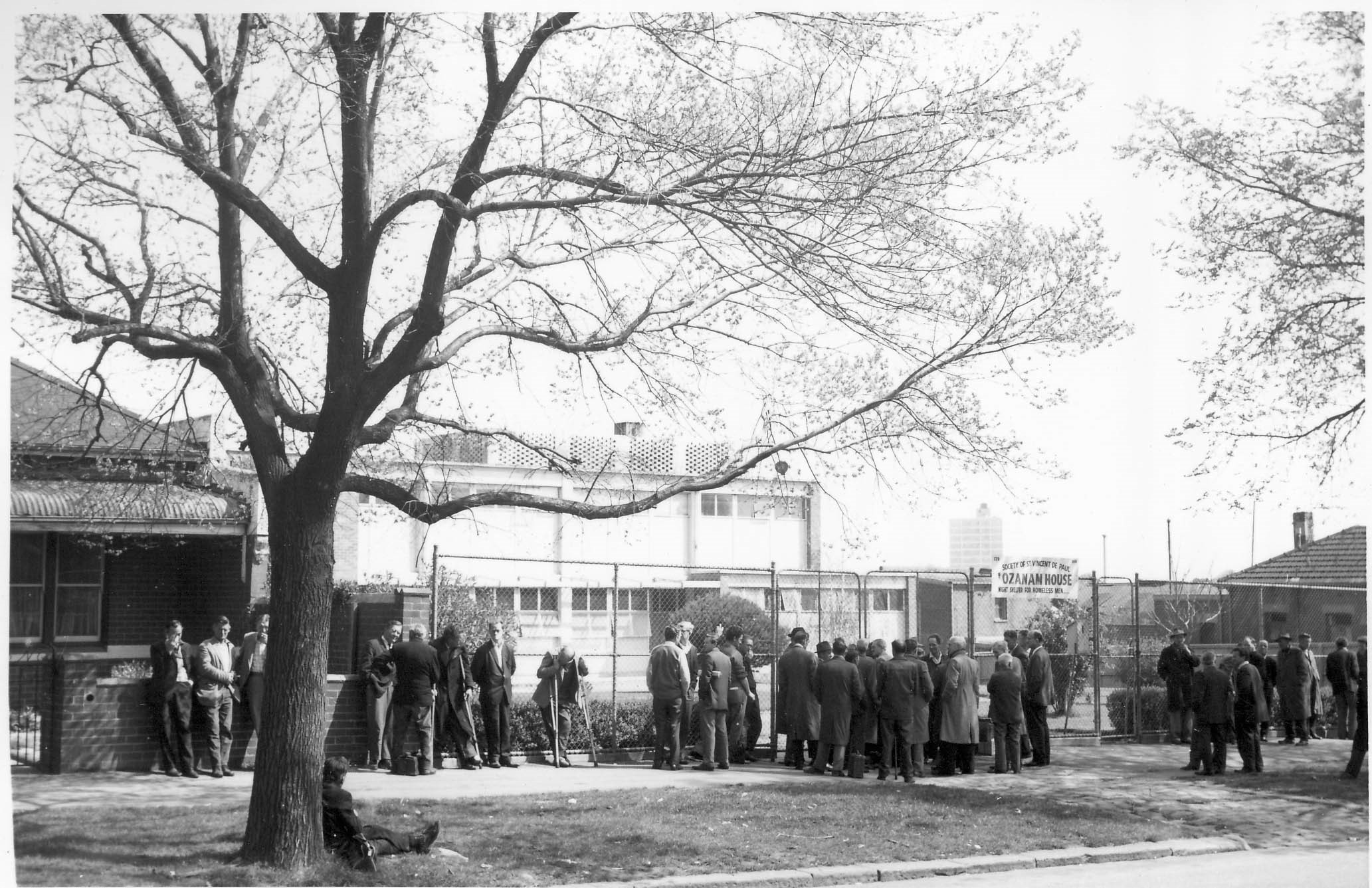

Ozanam House circa 1960.

The Congregate Crisis Supported Accommodation (CCSA) era had arrived, providing single rooms and significantly reducing the numbers of people on‑site. This delivered a dramatic improvement in privacy and amenity, and also enabled greater engagement with case management support and exit planning, with the former being mandated under new funding arrangements.

Some of the policies and practices within the night shelters were undoubtedly crude by today’s standards, however it would be remiss to think that the pre‑CCSA era was devoid of any innovation or purpose. The bones of many current homelessness responses can be traced back to the night shelters, and specifically to the energy, commitment and advocacy of those working within and around them.

At Ozanam House alone:

- A specialist aged‑care hostel (Bailly House) was built behind Ozanam House in 1973, for older men with a history of homelessness requiring permanent housing.

- An alcohol recovery program was initiated in 1975 by the board of management, who then commissioned a research team (including a psychiatrist, an academic and a social policy adviser), to model and implement on‑site support. A 12‑bed detox dormitory was then set aside for

interested residents and staffed by a nurse. Post‑detox, residents were supported to maintain abstinence on site (occupying another separate dormitory and attending Alcoholics Anonymous meetings). There was also the acquisition of independent housing in the Dandenong Ranges as an early step‑down model, under the rationale that it was important to remove men from the ‘temptations of the city’. - A regular on‑site health clinic had been established by General Practitioners in the 1980s (and possibly earlier).

- By 1990, a three‑member ‘welfare team’ was employed to source long‑term housing for residents, and in 1992 (immediately prior to the redevelopment), the team successfully sourced alternative housing for 220 residents.

Of course, over the past 25 years the ability of all providers of crisis accommodation to support people into appropriate, independent housing has been gradually eroded, most notably by the declining availability of social housing stock, and by issues of housing affordability more generally. At a local level, we have been also challenged by increasingly outdated and ill‑suited infrastructure. As any visitor to the previous building would attest, Ozanam House was pushed beyond capacity in regards to accommodating staff, access to private meeting spaces, use of technology, group spaces, clinical spaces, and managing health and safety; let alone enhancing a strengths‑based, person‑centred, trauma‑informed response.

Innovation in 2019

Just as the redevelopment of CCSA in the mid‑1990s lifted amenity and expectations to the community standards of the time, the current redevelopment of Ozanam House will establish a new value proposition for people accessing crisis accommodation from 2019. The overarching goal for the new building is to align with and support contemporary best practice, and to this end the new building is an essential enabler. However, there are also very practical and immediate benefits. The new design and infrastructure improves on‑site safety and will allow for the accommodation of women (a first for Ozanam House) in addition to improving culturally safe support for those who may be vulnerable in a congregate environment (for example, people who are LGBTIQ+).

Artist impression of the new Ozanam House redevelopment.

Parallel to the five‑year journey for the physical re‑design and new build, has been the development of a new service model. VincentCare’s Homelessness to Recovery Model (HRM) now anchors the development and delivery of VincentCare services consistently within Recovery principles such as hope and optimism, safety, choice, connectedness, aspiration, self‑efficacy, collaboration and community.

The HRM is described in four distinct and interrelated frameworks; Engagement, Coordination, Case Management and Participation. The frameworks operationalise the recovery principles and align the organisation with recovery focused objectives.

| Engagement | Coordination | Case Management | Participation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Creation of normalising and safe spaces | Immediacy and reliability of initial requests for assistance | Key Worker model for continuity | Protect and promote client rights |

| Positive reframing | Development of meaningful choices and options | Goal oriented and realistic | Activate roles and opportunities within decision making |

| Small cognitive restructuring | Identify and mobilise strengths and capacities through assessment | Clear role expectations and boundaries maintained | Expand and develop skills |

| Structured, purposeful, empathetic and predictable worker behaviour | Access to specialist services where identified | Celebrate efforts and achievements | Develop mechanisms for clients to contribute to organisational decision making and strategy |

The HRM and the physical redevelopment of Ozanam House has received a timely boost via the collaborative review of CCSA by the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and providers across 2015–2019. This has now culminated in the release of ‘innovation’ funding

to support and enhance service models. We have been able to leverage the significant research, evidence and practice wisdom that has developed in the homelessness sector since the previous commissioning framework was established, ground the new service models with the client experience,

and are no longer constrained by throughput targets. The work of Alison Fraser (DHHS Homelessness and Accommodation Support) in establishing and driving the CCSA review must be acknowledged.

Intensive and Portable Support

Key to the new approach at Ozanam House will be to deliver more intensive, targeted and portable support. Case management will be attached to the individual, and not the building or a person’s tenure of crisis accommodation. Six additional case managers/key workers will reduce caseloads from 15 to six, and importantly allow each key worker to support an additional three recently exited clients into the community. The underlying imperative is to maintain engagement and advocacy, and establish those essential links within the community that sustain independence.

Purposeful lengths of stay

Moving away from set lengths of stay and a culture of time-limited support, Ozanam House will instead focus wholly on people’s duration of homelessness and complexity of need. Local[1] and international[2] research identifies that people’s duration of homelessness is an important driver for service design, and responses should be based on support needs more prevalent within specific phases of homelessness.

The duration people have experienced homelessness informs significant variations in health, independent living skills, sense of personal identity, risks, social supports, exposure to trauma and abuse, confidence, trust and other intrapersonal capacities necessary to exit homelessness and rebuild independence. For the majority of CCSA clients who present with complex support needs, the new approach will signal longer durations of support, and require more frequent and intensive case management contact. For the minority of CCSA clients who can build or return to independence quickly, more intensive support over a shorter duration minimises exposure to the homeless service system, preventing further trauma and the development of adaptive behaviours. The goal here is to reconnect people to their community of origin or community of choice, where the opportunities to create social capital are greatest.

The new imperative is to remain sensitive to the changing capacity of the individual within the environment. Using their own Outcomes Measurement Tool Outcomes Star, the St Mungo’s in the UK have noted that most clients benefit from their time in crisis accommodation, and that positive outcomes peak between six and 12 months[3]. As such, additional exit planning and emphasis will be given to people who reach a six-month stay.

Consolidated and resourced health services platform

Opportunities for improved health, wellbeing and personal stabilisation have always been essential and relevant within crisis accommodation, and will remain a clear focus via the integration and planned expansion of health services from Ozanam Community Centre and Ozanam House, upon the one site.

With dedicated management and administrative support, the new facilities will provide a range of primary and allied health services, integrate AoD treatment responses, provide opportunities for multi-disciplinary care and increase health promotion opportunities. Targeted and free health service responses assists in the development of trust, and in turn this can be harnessed and extended into other domains, including housing support.

The primary and allied health profile includes the following programs;

| Health Program | Provider/Partner |

|---|---|

| General dentistry clinic | Dental Health Services Victoria |

| Denture clinic | Dental Health Services Victoria |

| GP clinic | St Vincent's Health / Brunswick Community Medical Centre |

| Nurses clinic | Bolton Clarke - Homeless Persons Program |

| Occupational therapy | VincentCare |

| Podiatry | VincentCare |

| Optometry clinic | Australian College of Optometry |

| Dietetics | CoHealth |

| Acupuncture clinic | Endeavour College of Natural Health |

| Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander health worker | VincentCare |

This list is the starting point for the redeveloped Ozanam House, with opportunity to expand both the range and frequency of services provided.

The AoD treatment profile includes the following service responses;

| AoD Program | Provider | Treatment Response |

|---|---|---|

| Brief Intervention Program (BIP) | VincentCare | Assertive engagement program supporting CCSA clients to reduce the harmful consequences of AoD dependency, providing practical and emotional support required for people to engage in formal treatment. |

| Substance Treatment and Recovery (STAR) Program | VincentCare Consortia with The Salvation Army – Adult Services (lead agency) | Performs the mainstream AoD service types; • Assessment • Counselling • Care and Recovery Coordination |

| Quin House | VincentCare | 11 bed post-detox residential program providing 12 weeks integrated counselling, peer support and accommodation for men experiencing homelessness and substance dependency. |

| Reconstructing Life after Dependency (RLAD) Program | VincentCare | Step-down case management program for clients who have completed the Quin House program, assisting them to maintain a substance-free lifestyle and independent housing in the community. |

Homeless Resource Centre

Transitioning Ozanam Community Centre to a Homeless Resource Centre within the redevelopment, aims to better target people not accessing homelessness assistance via the Access Points, through a more clearly defined mandate and focus on practical supports. The sequencing and availability of supports throughout the day will be designed to better engage people sleeping rough, commencing with a greater emphasis and window for the breakfast program. Showers, storage, laundry facilities remain essential components, and the Initial Assessment & Planning (IA&P) team will also be better resourced and improve the coordination of crisis assistance.

There is a lot of change, and there is also a lot of optimism that the structures are now in place to improve VincentCare’s response to a wider range and increased number of people experiencing homelessness.

Originally published in the March 2019 edition of Parity, the national magazine for Council to Homeless Persons.

[1] Johnson, G., Parkinson., S, Tseng, Y., & Kuehnle, D. (2011) Long-term homelessness: Understanding the challenge – 12 months outcomes from the Journey to Social Inclusion pilot program. Sacred Heart Mission, St Kilda.

[2] Van Doorn, L., Phases in the development of homelessness – a basis for better targeted service interventions, 2005, Homeless in Europe Journal

[3] Deloitte Access Economics prepared for Queensland Department of Communities, Service Models for Single Adults Experiencing Homelessness – Literature Review, 2011.