Chilly house? Mouldy rooms? Here's how to improve low-income renters’ access to decent housing

Poor quality housing can impact physical health, mental wellbeing and comfort. And it's more likely to affect low-income households.

People’s quality of life, their health and their comfort can suffer when living in poor-quality housing. It can also impose high ongoing costs of maintenance, repairs, heating and cooling. And these problems are more likely to affect low-income households, as our report for Shelter NSW shows. In it, we review the evidence on housing quality problems and consider ways to resolve these, especially for low-income households.

There is extensive evidence of the impacts of poor-quality housing on physical health, mental wellbeing and comfort. For example, poor design and maintenance can lead to the build-up of mould.

Read more:

Is this a housing system that cares? That’s the question for Australians and their new government

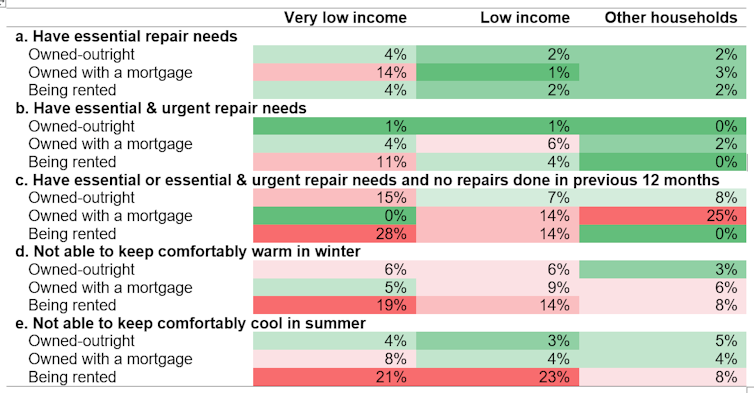

These negative impacts vary by income groups and tenure. From the recently completed Australian Housing Conditions Dataset we know, for example, that renters on very low incomes (the bottom fifth of households for gross income, about $20,000 a year) are most likely to have unmet repair needs. They also have a harder time staying comfortable during winter and summer, as the table below shows.

What are the reasons for poor-quality housing?

There are several underlying reasons for substandard housing.

Properties may enter the rental market after years in owner-occupation with no formal checks on their state of repair.

Another problem is some private renters do not assert – or feel unable to assert – their legal right to habitable premises in a reasonable state of repair and upkeep. This is often because of the insecurity of their leases and lack of affordable alternative housing.

Read more:

Life as an older renter, and what it tells us about the urgent need for tenancy reform

Another issue is “split incentives” – landlords decline to upgrade properties because they would not receive any benefit themselves.

There are also problems in public housing. Disinvestment by governments has both reduced the supply of housing and caused a backlog of maintenance for much of the remaining stock of dwellings.

Read more:

Tenants’ calls for safe public housing fall on deaf ears

Housing quality is covered by myriad regulatory regimes. Lately, governments have been focused on questions of how best to regulate construction of new buildings. Less attention is given to the ongoing use of existing buildings.

Recent state and national reviews have highlighted problems in the certification of building design and construction, and in the public agencies that oversee the certifiers. Some state governments have begun to respond. The New South Wales government, for instance, is moving to consolidate the regulation of construction practitioners under a new building commissioner.

We spoke to a range of housing sector stakeholders and the theme from the recent reviews that most struck a chord was inadequate policy governance. There was no comprehensive overview or oversight of the issues of housing quality. As a result, some important issues escape policymakers’ attention.

Many stakeholders indicated that the current focus on problems in new buildings is an example of this. Although that’s plainly an issue in need of attention, other problems in existing buildings and more fundamental solutions are being overlooked – such as increasing social and affordable housing supply.

Read more:

Australia needs to triple its social housing by 2036. This is the best way to do it

So what are the solutions?

Empowering tenants and regulators

One way in which the quality of existing housing is regulated is through tenancy laws. This will become more important as rental housing becomes an increasingly common option, particularly for the long term.

Recently, some state governments have amended tenancy laws to specify “minimum standards” for rental housing. Our research participants supported these moves, but said security of tenure also had to be improved to protect renters when they assert their rights. The onus of legal enforcement could also be shifted from tenants to regulators.

Mandating improvements to overcome the split incentive problem

The split incentive problem for housing quality means some landlords are reluctant to pay for upgrades – such as insulation or other energy-efficient features – where tenants are the beneficiaries. As a result, renters, especially those on low incomes, are likely to be living in housing of lower standards or quality.

A potential solution is for governments to take the minimum standards approach and legislate energy efficiency and other improvements as mandatory. This is already commonplace overseas.

One of our workshop participants observed that “energy poverty” was another way of framing the policy issue that had proved compelling in overseas jurisdictions. While this framing had not had the same impact in Australia, this may be changing.

Improving transparency of housing standards

Social housing providers have a role in leading by example. Increased investment in social housing could contribute to improved quality across the housing system.

To this end, social housing landlords – particularly state and territory public housing authorities – need to be more accountable to tenants and the general public. Transparent reporting on property conditions, maintenance and tenant satisfaction, led by the social housing sector, can and should be rolled out as standard practice across the sector.

To do this, however, enough funding must be provided to reverse decades-long underfunding in the sector.

Collectively, these options can deliver more equitable housing outcomes, not only to low-income households but to all. The challenge lies in having the political and industry will to act on them.

Read more:

Australia needs to reboot affordable housing funding, not scrap it

![]()

Edgar Liu, Senior Research Fellow at City Futures Research Centre, UNSW; Chris Martin, Research Fellow, City Futures Research Centre, UNSW, and Hazel Easthope, Associate Professor, City Futures Research Centre, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.